The Traditional Marlovian Theory.

This is the excellent and even-handed Wikipedia page on the long prevailing theory that Christopher Marlowe wrote the works of William Shakespeare.

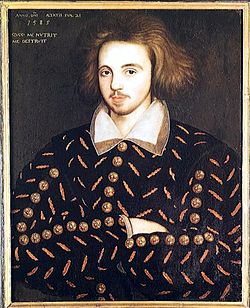

The Marlovian theory with regard to the Shakespeare authorship question holds that the famous Elizabethan poet and playwright Christopher Marlowe did not die in Deptford on 30 May 1593, as the historical records state, but rather that his death was faked, and that he was the main author of the poems and plays attributed to William Shakespeare.

Marlovians (as those who subscribe to the theory are usually called) claim that Marlowe's biographers approach his alleged death in the wrong way by trying to work out why he died, which leads to almost total disagreement. They say that a more productive question is what, in the circumstances, was the most logical reason for the meeting at which he was supposedly killed—and conclude that it would have been to fake his death. And if he did survive, they point to how universally accepted is Marlowe's influence on Shakespeare, how indistinguishable their works were to start with (surprising given their very different levels of education) and how seamless was the transition from Marlowe's works to Shakespeare's immediately following the apparent death.

Against the suggestion that his death was faked are that it was accepted as genuine by no fewer than sixteen jurors at an inquest held by the Queen's personal coroner, that everyone clearly thought that he was dead at the time, and that there is a complete lack of direct evidence supporting his survival beyond 1593. As for his writing Shakespeare's works, it is generally believed that Marlowe's style—and indeed his whole world-view—are too different to Shakespeare's for this to have been possible,[1] and that all the direct evidence in any case points to Shakespeare as being the true author. [2]

MARLOVIAN THEORY

The first person to propose that the works of Shakespeare were by Marlowe was Wilbur G. Zeigler, who presented a case for it in the preface to his 1895 novel, It was Marlowe: a story of the secret of three centuries [3] and the first essay solely on the subject was written by Archie Webster in 1923. These two were published before Leslie Hotson's discovery in 1925 of the inquest on Marlowe's death. Since then, there have nevertheless been several other books supporting the idea—a list is given below—but perhaps the two most influential were those by Calvin Hoffman (1955) and A.D. Wraight (1994). Hoffman's main argument centred on similarities between the styles of the two writers, particularly in the use of similar wordings or ideas—called "parallelisms". Wraight, following Webster, delved more into what she saw as the true meaning of Shakespeare's sonnets.

To their contributions should perhaps also be added that of Michael Rubbo, an Australian documentary film maker who, in 2001, made the TV film Much Ado About Something in which the Marlovian theory was explored in some detail, and the creation in 2009 of the International Marlowe-Shakespeare Society which has continued to draw the theory to the public's attention.

MARLOWE'S DEATH

For Marlovians, the arguments about his 'death' have changed over the years from (1) thinking that because he wrote 'Shakespeare' it must have been faked; to (2) challenging the details of the inquest to show that it must have been; to (3) claiming that the circumstances surrounding it suggest that the faking is the most likely scenario, whether he went on to write 'Shakespeare' or not.

In his Shakespeare and Co.,[4] however, referring to the documentation concerning Marlowe's death, Stanley Wells reflected the view of virtually all scholars that Marlowe did die then when he wrote: "The unimpugnable documentary evidence deriving from legal documents ... makes this one of the best recorded episodes in English literary history" and "Even before these papers turned up there was ample evidence that Marlowe died a violent death in Deptford in 1593."

THE INQUEST

According to the inquest on Marlowe's death, he died on 30 May 1593 as the result of a knife wound above the right eye inflicted upon him by someone with whom he had been dining, Ingram Frizer. Together with two other men, Robert Poley and Nicholas Skeres, they had spent that day together at the Deptford home of Eleanor Bull, a respectable widow who apparently offered, for payment, room and refreshment for such private meetings.

Two days later, on 1 June, the inquest was held there by no less a figure than the Coroner of The Queen's Household, William Danby, and a 16-man jury found the killing to have been in self defence. The body of this "famous gracer of tragedians", as Robert Greene had called him, was buried the same day in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Deptford. The Queen sanctioned Frizer's pardon just four weeks later.

Of those books or articles written about—or including an explanation of—Marlowe's death over the past twenty years or so, most of the authors, whilst accepting that Marlowe did actually die at that time, nevertheless believe that the witnesses were probably lying.[5] Usually they maintain that it was in fact a murder, not self defence, but Marlovians go one step further, and argue that if Frizer, Poley and Skeres could lie about what happened, they could just as easily have been lying about the identity of the corpse itself. In other words, that although they claimed it was Marlowe's—and as far as we know they were the only ones there in a position to identify him—it was in fact someone else's body that the jury was called upon to examine.

Some commentators have found details of the killing itself unconvincing.[6] There is no reason to doubt the honesty of the jury as a whole at Marlowe's inquest, however, so the witnesses' report to the jury was certainly plausible enough to satisfy them. Where Marlovians diverge from the orthodox approach is not to challenge the details of the tale apparently told by the witnesses, but to reframe the basic question from "why was Marlowe killed?" to "what was the purpose of the meeting?"

BACKGROUND

An important point for Marlovians is that Marlowe was in deep trouble at the time of his death. Accusations of his having persuaded others to atheism were coming to the Privy Council thick and fast and, whether true or not, he was certainly suspected of having written an atheistic book which was being used for subversive purposes.[7] For such crimes, trial and execution would have been almost guaranteed. Within the past two months, at least three people, Henry Barrow, John Greenwood and John Penry, had gone to the scaffold for offences no worse than this.

THE WITNESSES

Among Marlowe's close friends was Thomas Walsingham who, being the son of Sir Francis Walsingham's first cousin, another Thomas, had worked within Sir Francis's network of secret agents and intelligencers.[8] Marlowe also seems to have been involved in this sort of work, and was probably still in the employ of Lord Burghley and Sir Robert Cecil. As Park Honan says: "One may infer that (they) were inconvenienced by Marlowe's death".[9] Marlovians therefore find it significant that every person involved in the incident seems to have been associated in one way or another either with his friend Walsingham (Frizer and Skeres) or with his employers the Cecils (Poley, Bull and Danby).[10] The most likely reason for the get-together, they say, would have therefore been to save him in some way from the peril facing him. Killing him would hardly serve, so, given the dead body, they claim that the faking of his death is the only scenario to fit all of the facts as known. That Poley, Frizer and Skeres all made a living from being able to lie convincingly may have been relevant too.

THE CORONER

Support for the possible involvement of people in high places (whether it was to have Marlowe assassinated or to fake his death) has recently come to light with the discovery that the inquest was probably illegal.[11] The inquest should have been supervised and enrolled by the local County Coroner, with the Queen's Coroner being brought in by him only if he happened to know that it was within 12 (Tudor) miles of where the Queen was in residence (i.e. that it was "within the verge") and, if so, for it to be run by both of them jointly. Marlovians argue that therefore the only way for Danby to have finished up doing it on his own—given that it was only just within the verge, the Court in fact some 16 of today's statute miles away by road—would be because he knew about the killing before it actually occurred, and just "happened" to be there to take charge. If there was a deception, they say, Danby must have been involved in it and thus almost certainly with the tacit approval of the Queen. This does, of course, give as much support to David Riggs's theory that the Queen ordered Marlowe's death[12] as it does to the faked death theory.

THE BODY

If a death is to be faked, however, a substitute body has to be found, and it was David A. More who first identified for Marlovians a far more likely "victim" than had been suggested earlier.[13] On the evening before their 10 a.m. meeting at Deptford, at a most unusual time for a hanging, John Penry, about a year older than Marlowe, was hanged (for writing subversive literature) just two miles from Deptford, and there is no record of what happened to the body. Also of possible relevance is that the same William Danby would have been responsible for authorizing exactly what was to happen to Penry's corpse. Those who reject the theory claim that there would have been far too many obvious signs that the corpse had been hanged for it to have been used in this way, although Marlovians say that Danby, being solely in charge, would have been able quite easily to ensure that such evidence remained hidden from the jury.

MARLOWE AND SHAKESPEARE

The "Shakespeare" Argument

The mainstream view is that the author known as "Shakespeare" was the same William Shakespeare who was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, moved to London and became an actor, and "sharer" (part-owner) of the acting company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men, which owned the Globe Theatre and the Blackfriars Theatre. Most Marlovians are happy to accept these biographical details for the man known as "Shakespeare", and accept that people at the time probably thought he had written the works attributed to him. However, they believe that people may well have been deliberately deceived into thinking this, his having in fact been only a "front" for the real author.[14]

Generally speaking, Marlovians base their argument far less upon the alleged unsuitability of Shakespeare as the author—the approach favoured by most other anti-Stratfordians (those who challenge the belief that the works were by William Shakespeare of Stratford)—than upon how much more suitable Marlowe would have been, had he survived, than anyone, including Shakespeare. Marlowe was a brilliant poet and dramatist already, the main creator of so-called "Shakespearean" blank verse drama, and had precisely the education, the intellectual contacts, and the access to literature that one might have expected of the author of Shakespeare's works. Furthermore—given that so many unanswered questions remain over his death—if it really had been faked, they point out that he would have had far better reasons than any other authorship "candidate" both for continuing to write plays, and for being compelled to do so under someone else's name.

A central plank in the Marlovian theory is that the first clear association of William Shakespeare with the works bearing his name was just thirteen days after Marlowe's supposed death.[15] Shakespeare's first published work, Venus and Adonis, was registered with the Stationers' Company on 18 April, 1593, with no named author, and appears to have been on sale—now with his name included—by 12 June, when a copy is first known to have been bought.[16]

Stanley Wells again summarizes the reasons why Shakespearean scholars in general utterly reject any such idea: "All of this [documentary evidence of his death] compounds the initial and inherent ludicrousness of the idea that he went on to write the works of William Shakespeare while leaving not the slightest sign of his continuing existence for at least twenty years. During this period he is alleged to have produced a string of masterpieces which must be added to those he had already written, which no one in the busy and gossipy world of the theatre knew to be his, and for which he was willing to allow his Stratford contemporary to receive all the credit and to reap all the rewards."[17]

Internal Evidence

Style

As mentioned earlier, it is generally held in the academic world that Marlowe's style, themes, and indeed his whole world-view, are too different to Shakespeare's to allow the Marlovian claims and also that all direct evidence points to Shakespeare being the true author.

The styles of Marlowe and Shakespeare certainly differ in many ways. Some of these differences are only statistically apparent (see Stylometry), and some more immediately noticeable by the audience or reader. However, despite the fact that their ages were almost identical, there is little if any overlap of the periods when they were writing. This means that one cannot in either case be certain that these differences are because the works were written by two different people, as orthodoxy has it, or because they were written by the same person, but at different times, as Marlovians believe.

With stylometric approaches, for example, it is possible to identify certain characteristics which are very typical of Shakespeare, such as the use of particular poetic techniques or the frequency with which various common words are used, and these have been used to argue that Marlowe could not have written Shakespeare's works.[18] In every case so far where these data have been plotted over time, however, Marlowe's corpus has been found to fit just where Shakespeare's would have been, had he written anything before the early 1590s as all of Marlowe's were.[19] On the other hand, whereas stylometry might be useful in discerning where two sets of work are not by the same person, it can be used with less confidence to show that they are. This was something that T.C. Mendenhall, whose work some Marlovians have nevertheless thought proves their theory, was at pains to point out.

As for the less quantifiable differences—mainly to do with the content, and of which there are quite a lot—Marlovians suggest that they are quite predictable, given that under their scenario Marlowe would have undergone a significant transformation of his life—with new locations, new experiences, new learning, new interests, new friends and acquaintances, possibly a new political agenda, new paymasters, new performance spaces, new actors,[20] and maybe (not all agree on this) a new collaborator, Shakespeare himself.

Much has been made—particularly by Calvin Hoffman—of so-called "parallelisms" between the two authors. For example, when Marlowe's "Jew of Malta", Barabas, sees Abigail on a balcony above him, he says

But stay! What star shines yonder in the east? The lodestar of my life, if Abigail!

Most people would immediately recognize how similar this is to Romeo's famous

But soft! What light through yonder window breaks? It is the East, and Juliet is the sun!

when she appears on the balcony above. There are many such examples, but the problem with using them as an argument is that it really is not possible to be sure whether they happened because they were by the same author, or because they were—whether consciously or unconsciously—simply copied by Shakespeare from Marlowe. It is worth noting, however, that Marlowe is the only contemporary dramatist from whom he copies so much[21], and that the influence Marlowe had on Shakespeare is universally acknowledged.[22]

SHAKESPEARE'S SONNETS

The current preference among Shakespearean scholars is to deny that the Sonnets are autobiographical.[23] Marlovians say that this is because—other than the references to his name "Will" and a possible pun on "Hathaway"—there is no connection between what is said in the Sonnets and anything that is known about Shakespeare's life. In contrast, assuming that Marlowe did survive and was exiled in disgrace, Marlovians claim that the Sonnets reflect what must have happened to him after that.[24]

In Sonnet 25, for instance, a Marlovian interpretation would note that something unforeseen ("unlooked for") has happened to the poet, which will deny him the chance to boast of "public honour and proud titles", and which seems to have led to some enforced travel far away, possibly even overseas (26-28, 34, 50-51, 61). They would note that this going away seems to be a one-off event (48), and whatever it was, it is clearly also associated with his being "in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes", his "outcast state" (29), and his "blots" and "bewailed guilt" (36). The poet also says that he has been "made lame by fortune's dearest spite" (37). Each one of these segments, along with many other throughout the Sonnets, might be seen by a Marlovian as reflecting some aspect of Marlowe's alleged faked death and subsequent life.

Marlovians also claim that their interpretation allows more of Shakespeare's actual words to be interpreted as meaning literally what they say than is otherwise possible. For example, they can take "a wretch's knife" (74) to mean a wretch's knife, rather than assume that he must have really meant Old Father Time's scythe, take an "outcast state"(29) to mean an outcast state, not just a feeling that nobody likes him, and accept that when he says his "name receives a brand" (111) it means that his reputation has been permanently damaged, and not simply that acting is considered a somewhat disreputable profession. Jonathan Bate nevertheless shows why Shakespeare scholars claim that "Elizabethans did not write coded autobiography".[25]

CLUES IN THE PLAYS

Faked (or wrongly presumed) death, disgrace, banishment, and changed identity are of course major ingredients in Shakespeare's plays, and Stephen Greenblatt puts it fairly clearly: "Again and again in his plays, an unforeseen catastrophe...suddenly turns what had seemed like happy progress, prosperity, smooth sailing into disaster, terror, and loss. The loss is obviously and immediately material, but it is also, and more crushingly, a loss of identity. To wind up on an unknown shore, without one’s friends, habitual associates, familiar network—this catastrophe is often epitomized by the deliberate alteration or disappearance of the name and, with it, the alteration or disappearance of social status." [26]

Whilst noting the obvious relevance of this to their own proposed scenario Marlovians do not seek multiple parallels between Marlowe's known or predicted life and these stories, believing that the plays are so rich in plot devices that such parallels can be found with numerous individuals. On the other hand there are some places where they point out how difficult it is to know just why something was included if it were not some sort of in-joke for those who were privy to something unknown to most of us.[27]

For example, when in The Merry Wives of Windsor (3.1) Evans is singing Marlowe's famous song "Come live with me..." to keep his spirits up, why does he mix it up with words based upon Psalm 137 "By the rivers of Babylon...", perhaps the best known song of exile ever written?

And in As You Like It (3.3), Touchstone's words "When a man's verses cannot be understood, nor a man's good wit seconded with the forward child, understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room", apparently referring to Marlowe's death, are puzzled over by many of Shakespeare's biographers. As Agnes Latham puts it,[28] "nobody explains why Shakespeare should think that Marlowe's death by violence was material for a stage jester."

EXTERNAL EVIDENCE

The main case against the 'faked death' theory is that, whilst there is evidence for Marlowe's death, there is no equally unequivocal counter-evidence that he survived, or did anything more than exert a considerable influence on Shakespeare.[29] So far the only external evidence offered has been in the form of claiming that someone who was alive after 1593 must have been Marlowe, or finding concealed messages on Shakespeare's grave, etc.

Identity after 1593

Various people have been suggested as having really been the Christopher Marlowe who was supposed to have died in 1593. Some examples are a Hugh Sanford, who was based with the Earl of Pembroke at Wilton House in Wiltshire,[30] a Christopher Marlowe (alias John Matthews, or vice versa) who surfaced in Valladolid in 1602,[31] and a Monsieur Le Doux, a spy for Essex, but working as a "French tutor" in Rutland in 1595.[32] There was also apparently an Englishman who died in Padua in 1627, and said by the family he lived with to be Marlowe (even if this was not necessarily the name by which he was generally known), but no search has as yet come up with any confirmation of this,[33] and if Don Foster's hypothesis is correct that the "begetter" of the Sonnets may have meant the poet himself,[34] then Marlovians would assert that "Mr. W.H." was not a misprint, as Foster suggests, but merely showed that the identity being used by Marlowe in 1609 (including the name "Will"?) most probably had those initials too.

HIDDEN MESSAGES

Unlike some supporters of the Baconian theory, Marlovians in general do not spend much time searching the works for hidden messages in the form of acrostics or other transposition ciphers. Peter Bull does claim to have found just such a message deeply concealed in the Sonnets,[35] but few Marlovians have been convinced by this.

Furthermore, at least two Marlovians—William Honey[36] and Roberta Ballantine[37]—have taken the famous four-line "curse" on Shakespeare's grave to be an anagram. Unfortunately, the fact that they came up with different messages demonstrates the weakness of this approach. Anagrams as such are useful for conveying hidden messages, including claims of priority and authorship, having been used in this way, for example, by Galileo and Huygens,[38] but—given the number of possible answers—are really of use only if there can be some confirmation from the originator that this was the one he meant.

Many anti-Stratfordians have spent their time in search of letter-based ciphers for the hidden messages which they are sure must be there. On the other hand, a favourite technique of the poet/dramatists of the time was irony, the double meaning or double entendre—i.e. playing with words.

To combat those who claim that Shakespeare was not the real author of the works, orthodox scholars cite the First Folio—such things as Jonson's saying that the engraved portrait "hath hit his face" well, that he called Shakespeare "sweet Swan of Avon", and that it refers to when "Time dissolves thy Stratford monument". Yet according to Marlovians it is possible to interpret each of these in a quite different way too. The "face", according to the Oxford English Dictionary (10.a) could mean an "outward show; assumed or factitious appearance; disguise, pretence". When he writes of "Swan of Avon" we may choose to take it as meaning the Avon that runs through Stratford, or we may think of Daniel's Delia, addressed to the mother of the First Folio's two dedicatees, in which he refers to the Wiltshire one where they all lived:

But Avon rich in fame, though poor in waters, Shall have my song, where Delia hath her seat.

And when Digges writes "And Time dissolves thy Stratford monument", one Marlovian argument says that it is quite reasonable to assume that he is really saying that Time will eventually "solve, resolve or explain" it (O.E.D. 12), which becomes very relevant when we see that—whether the author intended it or not—it is possible to re-interpret the whole poem on Shakespeare's monument ("Stay Passenger...") as in fact inviting us to solve a puzzle revealing who is "in" the monument "with" Shakespeare. The apparent answer turns out to be "Christofer Marley"—as Marlowe is known to have spelt his own name—who, it says, with Shakespeare's death no longer has a "page" to dish up his wit.[39]